Before we get started with this little article, I do want to apologize for the long absence – back in January I got a job as a full-time museum curator! It’s extremely rad, but the adjustment threw me off my game with the site and channels, and I never really recovered. We’re working towards it now, though, so with a bit of luck there’ll be more in the back half of the year for you all to enjoy!

Over the past 5 years of running Ludohistory (has it really been 5 years?), I’ve played a lot of different games, set in a lot of different places. While I like to think I’m pretty knowledgeable, I am not an expert in most of the time periods that I cover on the channel!

That makes it hard to talk about the history.

While I can’t name everything that ever happened, I do have a lot of research experience, and a well-developed toolkit to find the answers quickly. So, even if something comes up that I have no idea about, I’m able to get to a “mostly true” answer pretty fast.

I’ve gotten asked a couple of times how I do that, so let’s talk about it. I have 4 steps that I go through when playing a game: Describe, Question, Evaluate, Interpret. This isn’t the only way to go about researching something (Adam Chapman and Jeremiah McCall, among many others, have much more structured tools to understand how historical games work!), but this is mine.

Step 0: Read.

Okay, I know I just said that I have 4 steps, but let me cook here.

The 4 steps I’ll outline below work very well as a way to “spot check” a game, but they work better with at least some baseline level of knowledge. I’m not saying that you need a Master’s Degree (or 2) of historical training, but you do need to know the basics of the setting!

For me, this can take anywhere from 10 to 50 hours of work. For a game like Last Train Home, there’s a lot of good info on the First World War and the Russian Revolution, so it did not take a lot of time to find sources from JSTOR, Google Scholar, or a trusted institution like the Imperial

War Museum. For The Thaumaturge, it took me quite a bit longer to understand the complex of magical practices in Russian Poland.

It’s not necessary to spend as much time as I do on this step, but I have to emphasize: read several different sources. Ideally, these are sources that pass some vibe checks:

they’re recent

they’re by a scholar with relevant credentials,

they’re published somewhere reputable, and

they reference a large number of primary sources

This doesn’t mean that someone needs access to fancy academic journals in order to succeed – I don’t! Museums, UNESCO sites, podcasts, and even YouTube channels can work to do this. Nothing replaces a good book, though, so try and get at least one of those.

This isn’t really a unique step – reading is an eternal part of doing analysis. It occurs throughout every other step of the process, and hopefully it remains fun! The goal, after all, is to learn something, and if a game inspires you to start learning, chase that feeling down as far as you can.

Once you feel okay that you will at least understand some of the references, then it’s time to start playing.

Step 1: Describe.

The first thing I do when playing a game for “research” is…. Play the game. That probably sounds obvious, but it’s actually surprisingly easy to forget. The games industry is just filled with trailers, behind-the-scenes blog posts, reviews, ragebait, LPs, and more. That makes it very easy to develop an opinion about a game without actually experiencing it for yourself.

This is a problem.

“Play” here is not an idle act – do not play through the game like you would casually. Instead, I tend to try to do a “wrongplay” (I term I borrow from Dan Floyd, a professional game animator and YouTuber). In short, I’m behaving in unexpected ways to find the limits of a game (though you still do need to make progress).

While I am playing with intention (that is to say, playing with the goal of learning something), I am not playing to “prove” anything. I am merely gathering data, to understand what the game is doing. Take notes! Or record your playthrough and be willing to watch the footage back. If you don’t hate hearing the sound of your own voice.

Step 2: Question

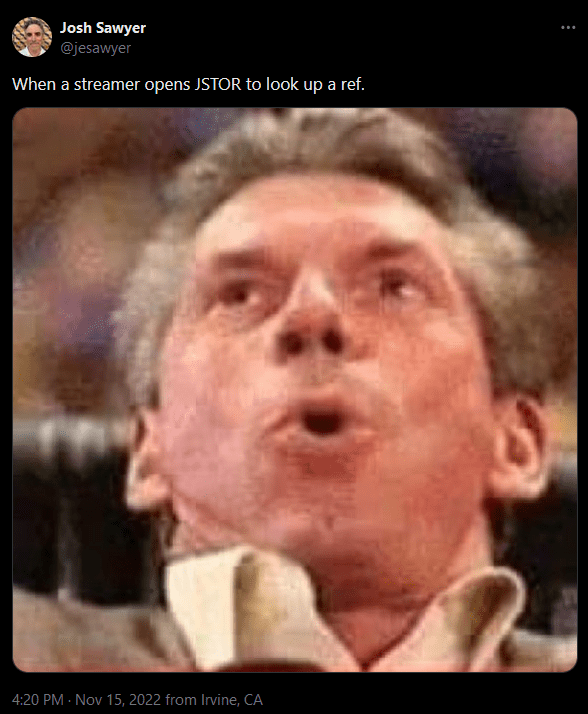

On my Twitch streams, we have a redemption for “Research Time.” That means that, if someone sees something in the game that they don’t understand, we can pause and go look for it together.

The act of pausing is the question. Why are they using greatswords? Is that a real historical person? What’s “Flyting”?

Questions do not need to be grandiose. In fact, in this context, the more specific they are, the better! A question like “is the game historically accurate?” is inevitably going to have the answer “sometimes.” “Sometimes” is not a satisfying answer, so don’t put yourself in that situation. Our Research Times are meant to be things that can be answered in 5 or 10 minutes. I’m a professional yapper, and sometimes the questions we ask have very little scholarship on them, so it can take longer, but that’s the sort of scope this phase should aim for.

On the flip side, “is this a real historical figure” isn’t actually a great question. “Is this a historical figure, and if so, how does the game’s characterization compare to our historical record” is much better. “Is this a historical figure” can be answered in about 5 seconds. Google their name, see if there are references outside of the game’s wikis, and you’re done. “How do they compare to the historical record” requires quite a bit more work, but is going to give you a much stronger result.

At this stage, though, we do not yet have an answer to these questions – focus on asking a good question that is both answerable and specific, then we can hit the books again.

Step 3: evaluate.

Once I have a well-formed question derived from the game, I’m able to go find some scholarship to help answer it. On-stream, I don’t really do my due diligence, sticking to one major source that seems representative to me. Reading silently makes for terrible content!

The best practice, though, is to compare a handful of different sources to make sure that you’re getting an answer that is grounded in scholarship. If you’re not already a trained academic, though, even starting can be overwhelming. So here are a few tips.

Use an academic search engine – JSTOR, Google Scholar, ProQuest, and ResearchGate are a few examples of search engines that prioritize published scholarship instead of web pages. If you have a physical book instead (some of us still like paper, okay?), use the index in the back in the same way

- Use fewer search terms – It’s tempting to copy-paste the entire research question into your search engine of choice. Don’t do this, and instead use just the central keywords. Search engines look for anything that contains the words in your search, so terms like “what” and “of” will add a lot of irrelevant things to your results. If you need to look up a name like “Richard the Lionheart”, put the name in quotation marks to tell the search engine to look for that sequence of words, instead of any of them individually.

- Don’t give up – Especially with Google Scholar, you may find the title of a relevant article but not the text itself. That’s okay! Once you have the title, you can search in regular Google for that entire title to see if the author has uploaded it to academia.edu or something. Or if you really have time, email the authors and ask for a copy. Yes it’s scary, but odds are they’ll just be happy anyone is interested in what they’ve written.

Step 4 – interpretation

As you go through the game, you may have steps 1-3 loop quite a few times! You’re playing the game, finding things that seem weird, and doing research to answer those questions. That is, effectively, a lot of really good qualitative (i.e. non-numerical) data about how the game “does history.” This step is where you put it all together!

With some luck, some patterns start to emerge in that data. If you’ve been looking at the tech tree in Civilization, for instance, maybe there’s something to say about how technology intersects with religious monuments. If you’re looking at the use of a Gothic cathedral in A Plague Tale, there’s an awful lot of 19th century “Gothic” horror influencing how we perceive the space. If you’re playing The Thaumaturge, the use of stereoscopes might stand out as a way to incorporate archival photographs into a game world.

Those are just a handful of examples, but they show how small rounds of research can develop into larger theses. Games do stuff, and the ultimate goal of this research is to have something to say about that stuff.

This is, in my opinion, the fun part! Games are, even more so than most media, subjective experiences, and using your interests to figure out something that makes a historical game work (or fail to work!) as a simulation is very fulfilling!

It also, in my opinion, has made me a better historian. Part of the historical method is the claim that “every source has a bias.” That’s well and good on paper, but for a lot of well-studied topics, so much work has been done that you can kind of just…. Accept what other people have said about the bias in the sources and be on fairly safe ground.

If you’re like me and play Weird Indie Games ™, that’s not a luxury you get. Nobody has studied the vast majority of the games I have played in my “career” on the web (what a strange thing to call this website…). So, any potential biases (read: creative choices) that exist within the game are on me to figure out. If I can’t articulate what their angle is, and in turn what my own angle is, I won’t be able to complete this step in a satisfying way.

Luckily, I do know that games are, first and foremost, meant to be fun (argue about what “fun” means in the comments). So, developers are often making creative choices that they believe will make gameplay more active, more immersive, more enjoyable for players. The things they include, and the things they leave out, spoil what they find fun. Does Assassin’s Creed Valhalla really think that 9th century Gloucestershire was a pagan enclave in the heart of Mercia? I certainly hope not! Did the devs clearly love The Wicker Man and thought an homage to it would be fun? Yep! Were they right? *unintelligible vaguely Welsh noises*.

Concluding thoughts

Lots of people, especially in the depths of hell that passes for social media, will react to this with “why should we care? It’s just a game don’t take it so seriously.” I won’t offer a defense, because that’s silly. You chose to click on this, I’ll assume you, like me, have a reason to do it. Personally – it’s fun, and it gives me an excuse to look into things I’d never look into otherwise. I don’t think it needs a deeper explanation. Curiosity is a fundamentally human thing, and I don’t think indulging it needs justification.

Whatever your reasons, I hope this little peak behind the curtain into how I organize my thoughts on-stream has been helpful! If you want to see it in action, make sure you follow over there! I stream less than I used to, thanks to that teeny tiny professional job thing, but Assassin’s Creed Shadows is coming out soon and I’ll be back in full force by then!

See you soon!

Ludohistory is made possible only through your support. If you enjoyed this post and want to support the channel, please do consider joining on Patreon.

Leave a comment