Everywhere we look these days, it seems like we’re surrounded by “AI.” Google shoves it to the top of search pages, fake images are flooding reddit and bluesky, Disney is allowing it to use Mickey Fucking Mouse. Even game studios are using it, with Larian’s Swen Vincke announcing their upcoming Divinity was using it and Square Enix insisting that AI can replace QA testers.

The fundamental technology of “generative AI” – ultimately, a number generation algorithm – is not new. It’s been used in everything from hearing aids to animation studios for a long time. What is new is how obsessed every tech company is with it, heralding it as “Something We Cannot Do Without” and “Definitely Not A Bubble, We Promise.”

I’ve made no secret of the fact that I think ‘generative AI’ is harmful to every facet of human existence. Much has been said about its environmental harm, its degradation of labor, the psychological harm it inflicts on users, its mass plagiarism, its inefficacy, its worsening hallucination problem, etc. etc. And rightly so! Those things suck! Particularly frustrating, though, is that one of the few use cases that is gaining acceptance is to use it for work is “brainstorming.”

Take Nihon Falcom, the studio behind “Trails in the Sky” and “Ys.” In a recent investor meeting, they said “We are proceeding cautiously due to legal considerations. We are actively using AI for brainstorming scenarios, conducting research, and similar applications. Tasks that previously took 2-3 hours can now be completed in 10 minutes. AI also handles proofreading for typos and errors in scenarios.”

At first glance, this seems…. Reasonable. Cautious, even. Certainly, it’s a step better than letting it manage critical software and then watching it delete everything! On second glace, we should be alarmed by it.

Let’s turn to history to see why.

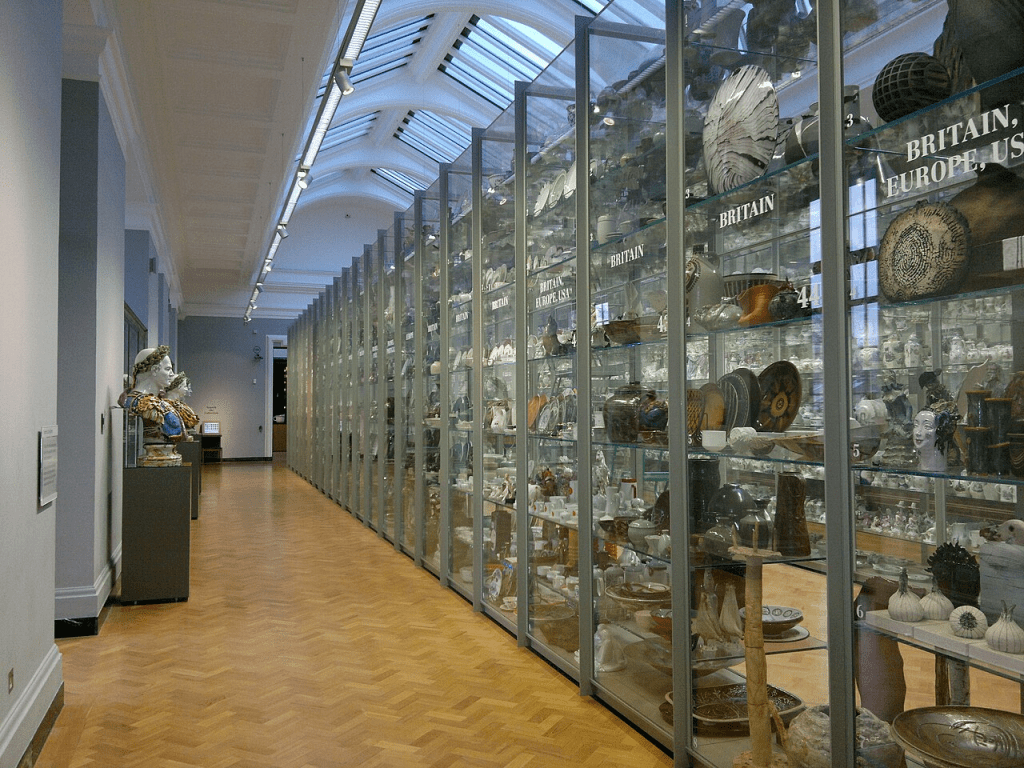

At its core, historical research is based on the archive – a repository of documents from the past. Archives collect, sift through, and make accessible those works, but rarely read through them thoroughly. The historian’s job is to read those documents carefully, and use them to construct an evidence-based story about what the past was like. (Museums are similar, but they protect the objects of the past instead of the documents.)

It’s often tedious work, made worse by poor handwriting, exorbitant travel costs, and a strict ban on coffee and snacks. But, many historians will say it is their favorite part of the job. Directly interacting with the past is the thing that matters, and few joys can surpass the sense of awe when you discover something in there that nobody else knew about.

After spending time in the archive, the next step is what I like to call “sit and think really hard about it.” It takes time for ideas to percolate, for the shape of the narrative to take form. In that time, there might not be a lot of measurable output, but doing that sets you up to be more efficient later. If you know where you’re going, it’s easy to get there without getting lost, and you learn where you’re going by taking your time and letting the ideas take shape.

While game development is not historical research, the same principles apply. In fact, this is true of any project-based work. Long before there is a finished project, there have to be decisions made about setting, about scope, about focus. From those decisions come questions, and from those questions comes a need for research. If the fantasy kingdom is supposed to evoke Chinese architecture, well, you better start looking up what the Forbidden Palace looks like.

This is traditionally the role of concept artists and writers – they research, and from that research they create the outline of a believable world, which is then filled in by the rest of the programmers, artists, animators, etc.

ChatGPT might be able to answer the concept artists’ questions “well enough” – it sounds at least plausible, it links a couple images, and it uses the same keywords as the article you asked it to summarize. Now you have enough to get drawing. It might not be right, but hey, surely that’ll sort itself out eventually, right?

Right? Well, it hasn’t yet.

Even if it was 100% accurate, though, using AI deprives the team the chance to be surprised. It denies expertise and the value of practice. It denies going out and testing something for yourself. It denies you the chance to run into something that makes you go “holy shit that’s so cool, we have to put that in.” AI doesn’t really do “holy shit.”

At its absolute peak of Working as Promised, generative AI models ultimately do little more than say “yes” or “no.” There is no space for nuance and surprise, for the world around us to prove itself weirder than we can possibly imagine. That’s all synthesis is – the portrayal of an average. And ‘average’ is rarely the most interesting answer.

Research is creative work, and “genAI” cannot replicate creative work. Don’t let the robots trick you into thinking otherwise.

Leave a comment