We all agree – things suck right now, right?

A coup in the US, an intensifying climate crisis, a cost-of-living crisis with no end in sight, a genocide accelerating in the West Bank even as Gazans get a scant few weeks of peace, AI Bullshit making everything worse, intensifying racist and anti-trans policies in much of the world, and a media ecosystem that seems to not give a shit about any of that.

And here I am, playing games and talking history.

Is this just a distraction? Do I need to switch into being a news channel? How does this protect the people I care about?

What is the point of acting when the theater is burning down?

These are the thoughts that have come to mind in the past weeks, in my job as a museum curator and especially with this channel. I can go about my day, create my silly little exhibits, play my silly little games, and see almost no change in my day to day life. Even as the largest financial institution in the world gets compromised by teenagers, crucial health projects get shut down, and a slew of orders threaten generations of effort led by the most vulnerable people in society, I see little change out in the countryside.

I don’t really talk about contemporary politics on the channel, and even as I try to stay abreast of the news, the stream remains isolated from it.

Is that simply the luxury of my privilege?

In the midst of this crisis of confidence, I’ve thought about all the platitudes historians have leveled over the years trying to defend the field of history. Doubled with entertainment – and I am an entertainer as much as a teacher – an army of reasons in favor of spending time making art emerges. Unfortunately, I think many of those reasons suck. Let me list a few:

History teaches us about the present moment

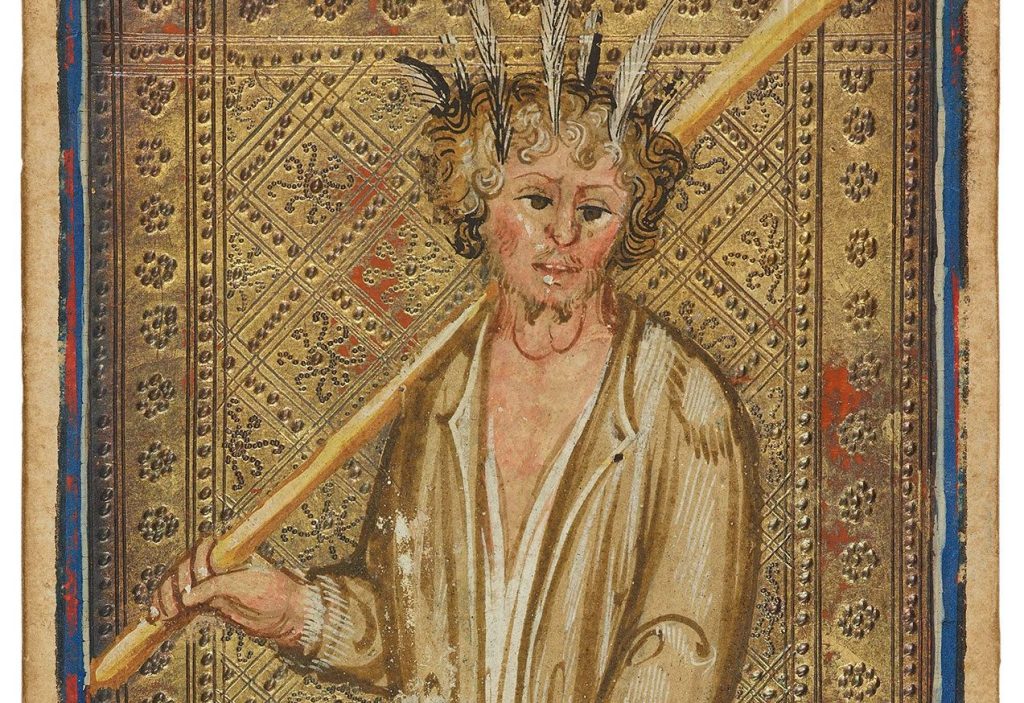

Maybe some history does. But it would be disingenuous to claim that all of history is relevant in that way. Histories of activism, of resistance, of human resiliency, of empire are all fascinating and worth studying. And there are people who are able to transform that research into useful lessons – there are some archival materials from World War Two that are circulating on social media right now that show an example of that! But 14th century Scandinavian hagiographies are also fascinating and are probably…. not that relevant to the ongoing state of the world. So I don’t think “history” as a whole does that.

Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it

this is just the last point but taken to absurdity. It barely even merits a response! And now more than ever shows us that knowing the past doesn’t mean we’re able to prevent the same traps.

History helps us hold tyrants accountable

I’m a firm believer that death is pretty final. If we only judge a tyrant after they have died, that won’t fucking help all the people they hurt while they were alive.

Escapism

This is maybe more the “games” than the “history” side, but like… people since JRR Tolkien have been defending escapism as something necessary. I sympathize, I think Tolkien’s values of solace and recuperation matter, but they rely on there being a return to reality. Crossing the border into the Other World doesn’t mean anything without a return! And with so many sources of escape in livestreams and hundred-hour games and bingeable TV, it’s easy to bounce from escape to escape and never return to the here and now.

Games teach us empathy

Games can put us into other people’s shoes and explore different perspectives. Theoretically. Many games have the subtlety of a brick to the head – Metaphor Re:Fantazio was literally a “fantasy” about fascistic manipulation of electoral systems and the intertwining of racism and fascism. Millions of copies sold, and how many people buried their heads in the sand and pretended it didn’t have lessons for real life? I don’t know, but I’m sure it was enough to be depressing. See also – gamergate 2.0. See also – every moderately-sized youtube comment section.

History is innately valuable

This is a weird amorphous blob of an argument. There’s some ephemeral, barely definable Good that history (or the humanities writ large) provides that justifies it without further apology. I just don’t buy it anymore. The ‘innate good’ does not provide a moral excuse for disengagement from the world, for hiding away from atrocity and abetting fascism. I think it is increasingly hard-pressed to justify the time it takes away from direct action.

As defense after defense crumbles, I start to feel like a jester in a crumbling tower, impotently jingling along through rubble. The abyss yawns before me, and I built no bridges, gathered no rope, and all I did will be obliterated without trace or memory.

—

Viking-themed media loves one verse out of the entire body of poetry composed a thousand years ago:

Deyr fé, deyja frændr,

deyr sjalfr it sama,

ek veit einn, at aldrei deyr:

dómr um dauðan hvern.

Cattle die, kinsmen die,

Even the self will die,

but I know one thing that never dies

the renown of a dead man’s deeds.

People imagine it captures this ethos of a long-gone culture, who values glory and triumph in the face of certain doom. But the truth is more complex – memory is a tricky thing, and heroes can be valorized and ostracized in the same breath. It takes active care, advocacy, and vigilance to protect someone’s renown. Left alone, it can vanish, or mutate into a perverse echo of the original truth. Just look at the Vikings themselves, and how they have been leveraged in the name of hate.

I also think the issue of renown misses the mark. Folks like Elon Musk seem to be obsessed with renown – everyone must know them, everyone must love them, and so they act like bored children. The fastest way to get attention is to cause problems, and being a shitheel on the Internet is certainly causing problems. Everyone knows who they are, but if that’s “renown” I want nothing to do with it.

Most people historically also do not get remembered! Of the Vikings who may have heard that verse, how many names do you know? Erik the Red or Leif Eriksson? Sigurd the Dragonslayer and the tragic Brynhildr? Ragnar Lodbrok and his sons?

What of their followers, their families, their descendants? Hundreds of thousands of people lost to time. Is renown such a durable thing, and was it really a concern to most people in the Viking world?

The truth is complex, and this is not a space to wander into very learned debates about Viking-Age folk culture and sociality. Please clap at my restraint. But that culture was not foolish, and value could not have been solely defined by fame and memory. They’re too fragile, too scarce. Translated into the lingo of today, I have come to think that “impact” measured by numbers, by adoration, by fan mail, by wealth is a trap. It promises us: “If only you achieve XYZ metrics, imagine how much good you’ll do. If only you convert your platform to the social causes you believe in. If only you influence the youths. If only you if only you if only you…”

Instead, I hope, worth is defined through other avenues. Burials where hand-crafted goods are given to the deceased, healed injuries, and remnants of ancient toys tell us that people valued and loved each other even when they weren’t celebrities. Those people were appreciated in their communities, and that is, perhaps, enough.

—

In Soviet Czechoslovakia, the secret police were everywhere. Ever since 1968, when tanks rolled through Prague’s streets, the country had been subject to stricter and stricter censorship. As the space of what creative pursuits were allowed shrank, the “underground” grew.

Young poets, barely out of school, gathered in shuttered apartments to share literature, talk politics, and write. Their works were typed out, bound with staples and string, and handed around person to person. These books, known as “samizdat,” were grounds for arrest, but still circulated and circulated. Among the milieu of music, poems, plays, and manifestos, the voice of one young man named Václav Havel became known. Havel would become the first president of a free Czechoslovakia, and his community helped stabilize the country and forge its modern paths.

Importantly, these underground movements were not just about organizing, though they undoubtedly did that. Nor were they purely escapist art communes, though they certainly created a lot. Instead, these gatherings were shaped by the interests of the participants, and made space to build friendships first and coalitions second.

That is, I hope, what I can do.

Creation is not inherently resistance. Art can be propaganda as well as critique. But in this historical moment, a community based in shared values of authenticity, respect, and enthusiasm, is inherently disruptive. That, to me, is a stronger defense – streaming, hanging out, learning together are means to an end. Caring for each other – that’s the goal.

I hope this community never has to go underground. In this era of the Internet, I don’t even know what that would look like! But to all of you who read this, in the face of the horrors, thank you. Don’t compromise your communities or your values, help where you can, and we’ll help lift each other up to continue to hope for a better world.

Ludohistory is made possible only through your support. If you enjoyed this post and want to support the channel, please do consider joining on Patreon.

Leave a comment