By Quinn Bouabsa Marriott

We called them the Franks. In unreckoned number, horse and foot, lord and commoner alike, they crossed the threshold to the east with a lust for war and plunder. Their ambition: to seize the holy city of Jerusalem…and all Bilad al-Sham beyond. […] These pages tell the story of our struggle, of the courage of great leaders who fought for our land and our faith.

The Chronicler, Cairo – 1426

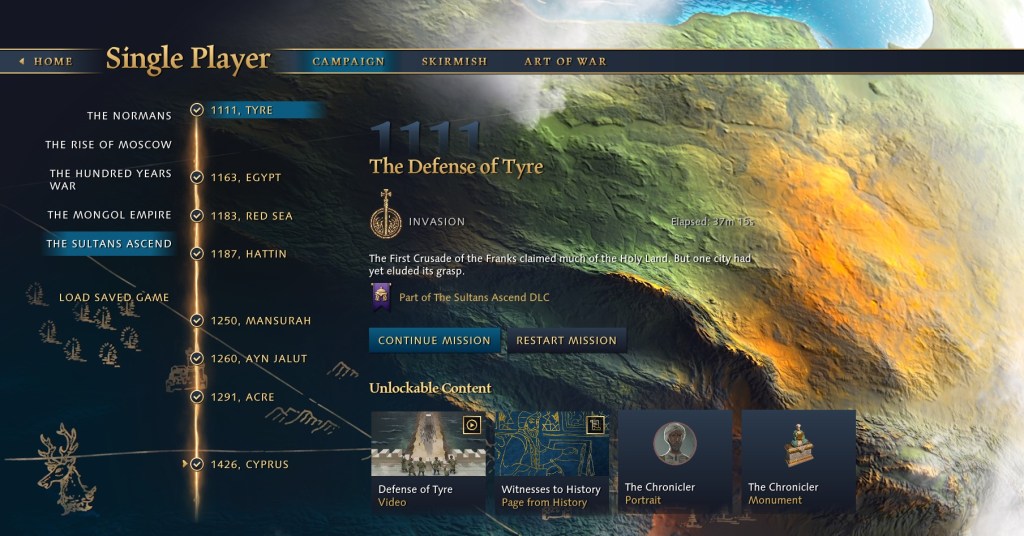

These are some of the opening lines to Age of Empires IV’s new campaign as part of its latest DLC, Sultan’s Ascend. Taking on the role of historic Muslim leaders, the game seeks to provide an Islamic perspective to the narrative of the Crusades.

Contrary to the base game where the player is guided by a modern ‘documentary-style’ presenter, this DLC’s narrator is much more tied to setting. Living in 15th-century Cairo, the narrator (identified only as ‘The Chronicler’) retroactively describes the events of the game leading up to his own time.

With additional pieces of historical context available after the completion of each mission, the game continues in its aim to be educational. Despite this, however, the entire campaign is told ‘in-character’ and serves as the narrator’s own historical account of Islamic encounters with foreign invaders, the crusading Franks, and how the Muslims came to eventually repel them.

The Campaign:

The campaign spreads out along three centuries. It starts at the beginning of the twelfth century, shortly after the First Crusade and the establishment of the counties of Tripoli and Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, forming the ‘Crusader States’. Moving towards the narrator’s own time, the campaign ends in the fifteenth century, when Muslims have supposedly regained supremacy over the Levant.

In between these two points, the game attempts to cover many of the major events in the history of the Crusades for the Islamic powers, primarily centred around two Egyptian groups: the Ayyubid dynasty and the Mamluk Sultanate.

Islamic Historiography:

At the start of the campaign, despite success in defending the city of Tyre, the narrator is unsatisfied. He shows contempt towards Muslim rulers for not doing enough in uniting against the Franks, some even joining with them. Our earliest Islamic chronicles for this period confirm this and indicate that Muslim rulers didn’t really see the crusaders as extraordinary, but, rather, as a new enemy that could be used against their rivals.

There were some critics to this inaction. The Damascene jurist, Al-Sulami, warned in his The Book of the Holy War that “This interruption [in waging jihad] combined with the negligence of the Muslims towards the prescribed regulations [of Islam]… has inevitably meant that God has made the Muslims rise up against one another”. This sentiment was echoed by later Muslim writers like Ibn al-Athir, Salah al-Din’s biographer (better known as Saladin). The Chronicler, therefore, mirrors a contemporary historiographic tradition.

While this feeling was shared among the religious classes, the idea of waging a united jihad, a holy ‘counter-crusade’, failed to gain traction among the military leaders of the time. As the narrator reveals, this changes under the atabeg of Mosul, Imad al-Din Zangi, who captured the crusader state of Edessa in 1144. He was succeeded by two leaders who continued to carry the mantle of jihad: Nur al-Din, and Salah al-Din, whose actions culminated toward the foundation of the Ayyubid dynasty, a critical Frankish defeat at the battle of Hattin, and the capture of Jerusalem in 1187.

The narrator’s account, however, would have us take a binary and linear perspective of these events as an inevitable clash of civilisations between Muslims and Christians. He drops some hints of further complexity, but fails to elaborate on them.

From the campaign, he omits the fact that Frankish cities and strongholds survived Salah al-Din’s victory over the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and that the Ayyubids were fairly content on maintaining the status quo with the remaining Franks. This was also a policy adopted by the Mamluks, who didn’t see an immediate need to actively attack the Franks until their later involvement with the Mongols.

There is also the game’s final mission, the invasion of Cyprus. Done in response to systematic naval raids on the Egyptian and Syrian coastline, the narrator is personally invested this time as it involves his family, who were taken prisoner. King Janus of Cyprus acts as a convenient scapegoat for the Chronicler to blame and condemn for launching these attacks, but his involvement with this piracy was nuanced. Janus had attempted to organise numerous treaties with the Mamluks, but with pressure from his own nobles and brother, Henry of Galilee, to promote piracy, combined with a decline in royal revenues, the king decided to renew raids on Mamluk territories.

The narrator presumes homogeneity in Cypriot society when there were many, especially among the merchant classes, who were opposed to war with the Mamluks. This included factions within the capital, Nicosia, such as the ‘White Venetians’ (Venetian residents) who not only opened the doors of the city to the Mamluks, but also showed them to the royal treasury.

The narrator’s agenda in retelling these events the way he does is obvious and his descriptions are authentic. Lacking the historical tools to critically assess his account, however, I’m left unsatisfied with this subjective Chronicler as an educator. He obscures a lot of details in a way many other of the game’s campaigns do not.

Women in Power:

An interesting feature of this DLC is the inclusion of a female character, Shajar al-Duur, available during the Battle of Mansurah. Originally a slave-concubine, she rose to become the wife of sultan As-Salih Ayyub, who died of illness in 1249 during the events leading up to the battle, the Seventh Crusade.

Shajar worked with her husband’s advisors and, according to the scholar Ibn Wasil, they “agreed to keep the event a secret from everyone” to maintain morale. In the game itself, despite possessing no battle capacity, the narrator makes it clear that, as the army’s main organizer, her spy networks were crucial for the battle’s success.

While the actual extent of her role is debatable, her adaptability in this crisis is impressive enough. It is a shame though that we see so little of her since she would go on to become sultan, an extraordinary feat for a woman in the Islamic world. Given the base game’s relative lack of female characters, however , this is a welcome addition. It opens up a platform to consider the role of women in more active political roles, an environment that is still strongly associated with men.

Takeaways:

Sultan’s Ascend provides a much-needed opportunity to review the history of the Crusades from non-European perspectives, which have long dominated the narrative, both in pop-culture and in scholarship.

It has also clearly learnt from the base game by deciding to add more playable female options, opening the floor for more nuanced understandings of how women could engage with politics and warfare.

The DLC’s major shortfall, however, is the narrative. As I have hopefully shown, although the use of a historical narrator has some amazing potential in showing players how medieval people viewed and constructed their own history, an uncritical exposure can equally mislead players. For it to have gone further as a historical experience, the campaign would have merited from providing tools to dissect the narrator’s account as a source in and of itself. This would have given players the freedom to examine the game as historians in their attempt to learn more about the world.

Bibliography

- Carole Hillenbrand, The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives (New York: Routledge, 1999)

- Jonathan Phillips, The Life and Legend of the Sultan Saladin (London: Vintage, 2020)

- Nicholas Coureas, ‘Latin Cyprus and its relations with the Mamluk sultanate, 1250-1517’, in The Crusader World, (ed.) by Andrian J. Boas (London: Routledge, 2016)

- D. Fairchild Ruggles, Tree Of Pearls: The Extraordinary Architectural Patronage of the 13th-Century Egyptian Slave-Queen Shajar Al-Duur (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020)

Ludohistory is made possible only through viewer support. If you enjoyed this post and want to support the channel, please do consider joining on Patreon.

Leave a comment